Maintenance as a Virtue

How can we understand virtue in a way that doesn't confuse it with personal achievement?

Thinking with the Berkeley Institute is the substack newsletter-blog for our community to engage in and extend the conversations we’re having. The theme “Virtue and the Intellectual Life” united our programming and conversations this Spring 2024 semester at the Berkeley Institute. We asked what virtue is, what it is for, and what place it has in both the university and in our personal lives. We invited staff and interns of the Berkeley Institute to contribute something about what they learned, what our conversations produced, and what our programming led them to think through.

Our Staff Assistant, Helen Halliwell, offers the following essay that both synthesizes some of our conversations and pushes them to the next level. She addresses the influence of “productivity culture” on the way that students can be inclined to understand virtue, and offers a contrasting perspective — considering, among other things, the journals of Gerard Manley Hopkins against the Autobiography of Ben Franklin.

Reflection after “On Aesthetic Habit: a Lenten Workshop” with Professor Katie Peterson and Professor Young Suh:

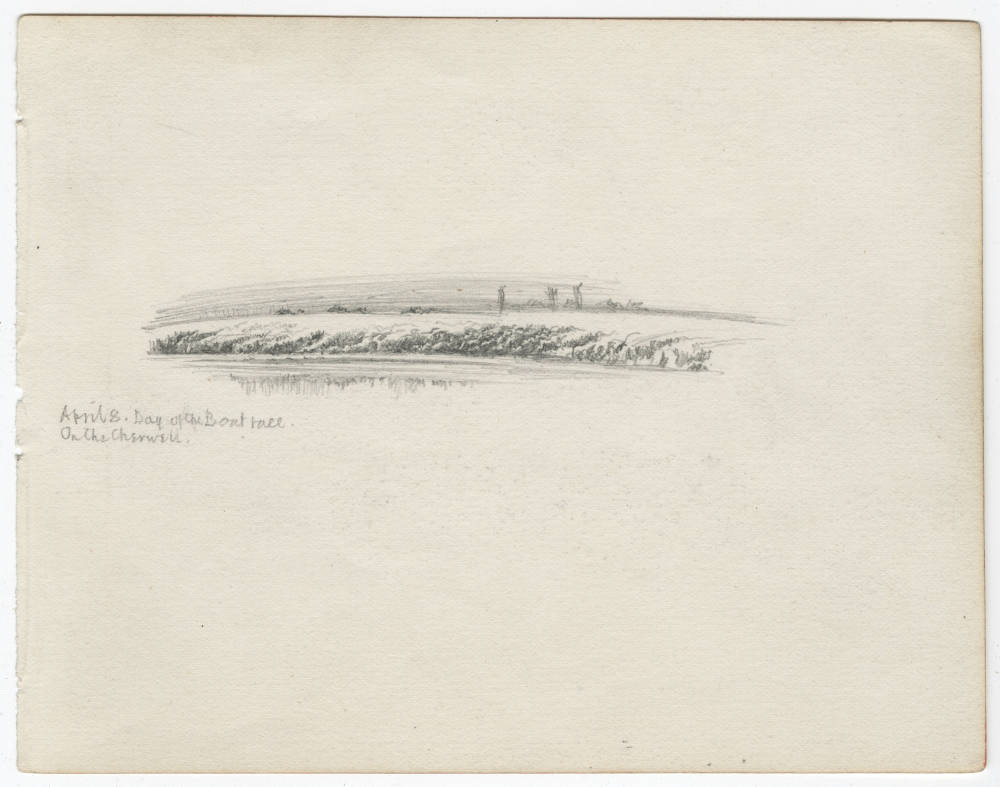

On a drizzly Saturday morning in February, Professor Katie Peterson read to us from Gerard Manley Hopkins’ journals. The excerpts recorded primarily two things: nature and the activities of his conversion (“It’s kind of thrilling,” Professor Peterson said). Motivated by Professor Peterson’s reading, I later acquired a handy Penguin edition of Hopkins. When I went to locate the same entries, however, I discovered that my edition had cut some lines, noted in bold here:

May 2. Fine, with some haze, and warm. This day, I think, I resolved.

May 5. Cold. Resolved to be a religious.

May 6. Fine but rather thick and with a very cold N.E. wind.

May 7. Warm; misty morning; then beautiful turquois sky. Home [Hampstead], after having decided to be a priest and religious but still doubtful between St. Benedict and St. Ignatius.

May 8. Dim sunlight; wind not cold, yet East.

May 9. Sultry and, I believe, dull.

May 10. Thick, but fine evening.

May 11. Dull; afternoon fine. Slaughter of the innocents. See above, the 2nd.

Why did Penguin decide that these lines weren’t worth the ink? While I forgive their editing for the sake of a more concise book, those entries do seem crucial in conveying exactly what’s so thrilling about the nature of the journal. In startling proximity, Hopkins’ unremarkable atmospheric observations sit alongside significant spiritual shifts. What is the continuity between these seemingly separate reflections on the external and the internal? And what can the proximity of these reflections tell us both about our relationship with the world and about how we think of ourselves?

How can we find a renewed, less results-driven way of attending to the objects and people around us as a practice of virtue in our lives?

In our conversations about virtue and the intellectual life at the Berkeley Institute, we’ve frequently come up against the restricting contemporary notion of virtue that is heavily focused on a product-oriented vision of self-improvement. We began our Virtue and the Intellectual Life reading group with excerpts from Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography that quickly framed this already familiar conception of virtue – one focused on achievement. With each successive reading group session, it became increasingly evident how difficult it is to shirk off Franklin’s utilitarian view of virtue precisely because of how deeply it saturates our contemporary culture, a culture that tells us a successful life is one that takes maximum advantage of time to achieve maximum accomplishment.

Because of this shadowy predominance of productivity culture, when we talk about what cultivation of virtues might mean for us now, it’s hard not to feel slightly allergic to language of self-optimization, efficient growth, and goal-setting. I wonder, then, with Hopkins’ diurnal attention to the weather in mind: how can we find a renewed, less results-driven way of attending to the objects and people around us as a practice of virtue in our lives?

The students and participants this semester brought with them great thoughtfulness to the topic of virtue. They were eager to try out whether certain unexpected attributes might be thought of as virtuous and entertained how they might work in support of our intellectual endeavors. Our conversations frequently had the refrain: “Can *such and such trait* be an intellectual virtue?” We considered courage, gratitude, the willingness to experiment, among many others. These surfacing questions signaled our search for thinking about virtue in a way that is compatible with our concerns as students, academics, or teachers who want to live meaningfully in the world — a world that insists we only look ahead at our productivity, our progress, our next steps. During one of our Undergraduate Working Group meetings on Work Ethic, a student expressed a wish to be able to procrastinate in a slow, deliberate way, rather than by impulsively consuming short-form content. Another student confessed that, actually, the focused workflow of a time crunch after procrastinating felt quite freeing and sometimes became the motivation for procrastination itself. Why is this the case? Do we crave focused attention so much that we might put off tasks and look away from them in order to obtain that focus later? We want to work well, we know we should be productive, and perhaps even desire to be so, yet we work counterintuitively against that ideal of productivity. While I was reflecting on Professor Suh’s and Professor Peterson’s workshop, I came across John Ashbery’s prose poem “For John Clare,” in which he identifies an “uneasiness in things just now,” a “[w]aiting for something to be over before you are forced to notice it.” This “waiting” seems to be exactly what many of us have settled into doing rather than noticing the object at hand.

The “aesthetic habits” that Professors Young Suh and Katie Peterson offered at their workshop might help us refine our search for actions that can cushion and inform our work and which don’t veer into obstructive or destructive productivity. The goal of many of these “aesthetic habits” was to realign something external with something internal, to engage with the world on a sensory level — whether visually, verbally, aurally, physically — in a way that clarifies something inside of us. At the event, we practiced a mindful photography technique, using our smartphones as a window to see anew something commonplace; we discussed forms of writing we could undertake that needn’t be shared, and if shared, only with one other person; we listed off our daily, reflexive habits and how we might note them instead (my favorite Lenten instruction from Katie Peterson: “wash your hands everyday with soap and think about it”). All of these suggestions are actionable ways to develop our own language of virtue because they encourage us to stop thinking about our own improvement and start thinking about the world around us.

Which is why Hopkins’ deleted meteorological observations are so important together with his personal reflection:

May 8. Dim sunlight; wind not cold, yet East.

May 9. Sultry and, I believe, dull.

May 10. Thick, but fine evening.

“Not cold, yet … and, I believe, … but fine…” We can see in these short conjunctive phrases Hopkins re-collecting, attuning, and realigning himself in the minutest of ways to what is external to him, not once or twice when the mood strikes him, but habitually. And by returning to those immediate and recollective perceptions, Hopkins upholds something, opens a space for continuity between himself and the outside world: he maintains a relationship to the external. The word “maintain” originates from the Latin manus, “hand,” and tenēre, “hold,” which combine into some version of the sentiment, “to hold in one’s hand.” To hold in one’s hand is to consider. These moments in Hopkins’ journals are, according to a typical measure of “useful” reflection, unproductive work. He is not recording details about the weather for the sake of meteorological analysis, or other use; why does it matter that the day was fine or cold or damp? Reading back these entries is quickly boring but I think that also gets us to their significance. Professor Peterson noted that the practice of this kind of attention “needles Hopkins because it’s continuous with the rest of what he does” – that is, moving from spiritual decision-making to noting the weather is not as discontinuous as it first seems because it’s indicative of an interior maintenance, a consideration of both the internal and external that occurs, if not simultaneously, at least in tandem.

By remaining attuned, like Hopkins, perhaps we might participate in gradual continuous acts of consideration that aim not necessarily towards improvement straight away, but towards a kind of sustaining that may return us gently to the self. And perhaps remaining consideration-bound frees us to be receptive to and cognizant of change, whether spiritual, emotional, natural, or societal. To be needled into continuity, to use Professor Peterson’s words, is distinct from being result-oriented because in imitating the continuity Hopkins enacts, we are encouraged to participate in acts of returning: to work, to thoughts, words, information, conversations, observations. By maintenance, I don’t mean to imply some kind of interior gardening, weeding out the bad parts and keeping the good parts as if we already know how to distinguish between those, but rather acts of return and care towards the world around us that might be the prerequisite to other kinds of growth.

One of our undergraduate students this semester asked how they can learn and organize information meaningfully without becoming an information hoarder. I worry about this myself, too; it sometimes seems to me that I only read and forget what I read, and so I rush to underline, to pinpoint, jot down, collect. But learning happens in the return, and when I return to notes, either from a year ago or from two weeks ago, both forgotten, I find my world brightened by connections hitherto unseen. This is also what happens when we engage in acts of maintenance at the Berkeley Institute by returning to conversations: we reinvigorate latent lines of thought and hold each other in consideration and care for, as the poet Elizabeth Alexander wrote, “And are we not of interest to each other?”